Summary:

This webinar in Dec 2024 explored promising new immunotherapy treatments for metastatic cancer in dogs.

Immunotherapy harnesses the power of the dog's own immune system to fight cancer. While conventional therapies are not effective in cases of metastasis, immunotherapy offers the potential for long-term control and even eradication of tumors.

The webinar highlights successful case studies, ongoing research, and future directions for treating metastatic canine cancer with immunotherapy.

The Canine Cancer Alliance is actively supporting research to advance immunotherapy treatments for dogs.

Transcript:

Today we're going to talk about cancer metastasis and what options there might be once cancer has spread or metastasized.

Most vets will say that there are no treatment options. This is true of conventional therapies like chemo and radiation. But with newer immunotherapy, it may be possible to treat metastatic cancer, and we’re going to discuss what researchers are learning from clinical trials involving canine patients.

This is a picture of my dog Gus. Gus was diagnosed with osteosarcoma when he was eight years old. By random luck, a few years earlier, I’d met the researcher at the University of Pennsylvania working on immunotherapy for dogs with osteosarcoma and the CEO of a company commercializing the therapeutic vaccine at a conference in Washington DC, and had seen their preliminary clinical trial data, which was quite impressive.

And so I thought, “If Gus could get this vaccine, there’s probably a 50/50 chance he could actually be cured”.

As many of you know, osteosarcoma is extremely aggressive, and even with today’s surgery and chemo, almost all patients will end up with metastasis. Mostly to the lungs.

But unfortunately, the study had closed and wasn’t enrolling any patients. Gus’s oncologist reached out to the U Penn team multiple times. I tried emailing. But he never got the chance to get the vaccine immunotherapy treatment. Sadly about 13 months after the diagnosis, we lost him due to lung metastasis.

And that's, unfortunately, the fate of most dogs with aggressive tumors. Recurrence and cancer spreading is what end up taking our beloved dogs from us.

The median survival time is less than a year with the best standard-of-care therapy for osteosarcoma (surgery + chemotherapy). The majority of patients don’t even make it to 12 months.

But the good news is immunotherapy can help.

Immunotherapy works by activating the dog’s natural immune system to target cancer. And so the Listeria vaccine, which Gus unfortunately did not get, and the EGFR/HER2 vaccine, which Canine Cancer Alliance is supporting—can help extend dogs’ survival times and sometimes even lead to a full cure.

Now, for example, the EGFR/HER2 cancer vaccine is available at 11 locations around the USA to dogs with osteosarcoma, transitional cell carcinoma, and hemangiosarcoma. And early data is showing that it is helping dogs live longer than with conventional therapies alone.

There are also other immunotherapy options, such as Immunocidin, which is a bacterial therapy that stimulates the immune system, and autologous vaccines, which are vaccines made from cancer cells, actually tumor samples, because cancer has all these unique proteins.

What’s remarkable about immunotherapy is that the side effects tend to be much milder than conventional therapies. And if you get chemo or radiation, cancer-killing is happening when chemo molecules are finding cancer cells. And it stops doing the work when you stop giving it chemotherapy.

But with immunotherapy, if designed right, the adaptive immune system takes over. And there’s a memory created, and the immune system will continue to look for cancer cells and continue to kill cancer cells even after the treatment is finished.

It might just be two injections of vaccines or it might be IV infusions, like sometimes Immunocidin is used, but you can have long-term benefits. So, immunotherapy can help slow down and maybe reduce the chance of metastasis and recurrence.

But can immunotherapy help treat cancer that has already metastasized?

Cody was an early recipient of the EGFR/HER2 vaccine, and some of you have probably heard directly from Mike when he joined our webinar earlier. Cody had a very large metastasis in his lungs. He had already been treated with chemo and had an amputation. Mike lives in New Jersey, and he came across the Yale vaccine, EGFR/HER2 vaccine, and decided to take a chance and travel to Connecticut to get the vaccine.

He was told by the veterinary oncologist, “Hey, you know, we’re really not sure what to expect. It’s probably not going to help your dog.”

Several months after Cody received the two vaccine injections, Mike realized, “Cody’s still here.” Several months later, Mike took Cody back to Connecticut, and he had X-rays done, and the metastatic tumor in his lung had completely disappeared.

Ranger’s story is similar. Ranger also had amputation and chemo, and he also was on a clinical trial at Ohio State University. But his tumor kept on growing— metastasized lung cancer. They came across the Yale vaccine, and they were lucky enough to get the vaccine treatment early on, and his tumor completely disappeared from the lungs.

Both Cody and Ranger lived for over three years, and osteosarcoma did not come back. Unfortunately, they did end up getting a different type of cancer—hemangiosarcoma—and passed away, but they were able to enjoy roughly three years of very high-quality time with their families.

The EGFR/HER2 doesn’t help all dogs with metastasis. We don’t know exactly why it helps some dogs and why it doesn’t, but we do know that the vaccine does help slow and reduce the chance of metastasis.

Now, there are also studies that show that metastatic osteosarcoma patients can be treated by repurposed oral drugs. And the reason that these oral drugs are used is because when cancer grows, it protects itself in a very special microenvironment. It will actually make a protective environment that the cancer-killing immune cells have difficulty penetrating, and it’ll fill the environment with immune cells that suppress immune activity.

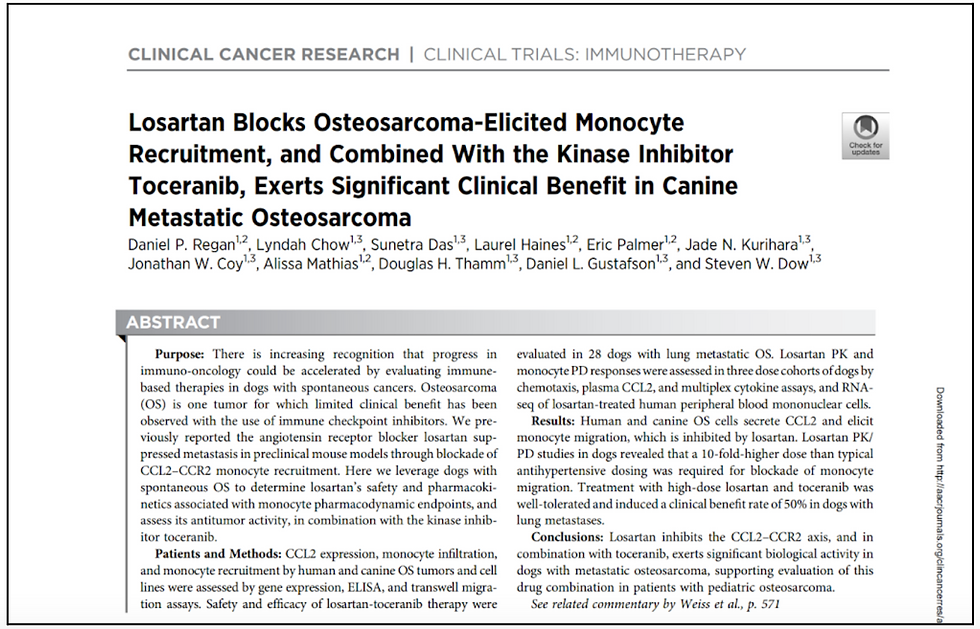

Molly was diagnosed with osteosarcoma and became a patient at Colorado State University. The veterinary research team there had a couple of oral drugs that were candidates for modifying the tumor microenvironment. A couple of them are blood pressure medications that are widely available. They knew that Losartan could actually have the beneficial effect and act against cancer, but they realized that they had to dramatically increase the dose of Losartan.

Molly was the first dog with metastatic osteosarcoma who responded well to Losartan, and her metastatic lung cancer—lung metastasis—began to shrink. But also, when they started combining Losartan with another blood pressure medication called Propranolol as well as Palladia, which is also called Toceranib, they could get a better response with dogs with metastatic tumors.

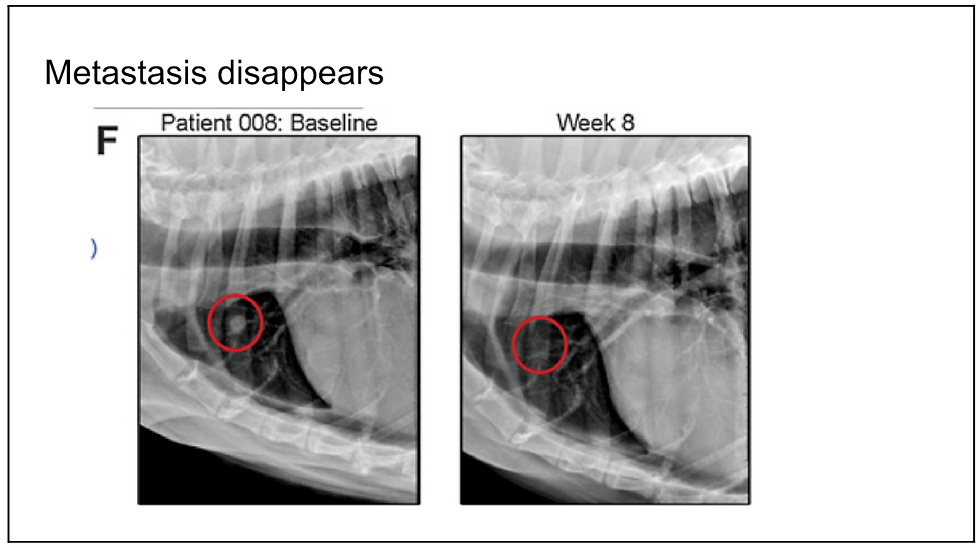

For example, Scout here had an amputation, and he went through chemo, but unfortunately, his cancer came back in the lungs. But when he got the Palladia-Losartan-Propranolol combination, the metastatic tumor in the lungs completely disappeared.

And here’s a picture example before this oral drug treatment started and then week eight, when the lung metastasis has disappeared.

This paper by Stephen Dow and Dan Regan and their professors at Colorado State describes some of the data from this trial. So it’s the combination of these drugs stopping these immunosuppressive immune cells from being drawn into the area around the cancer.

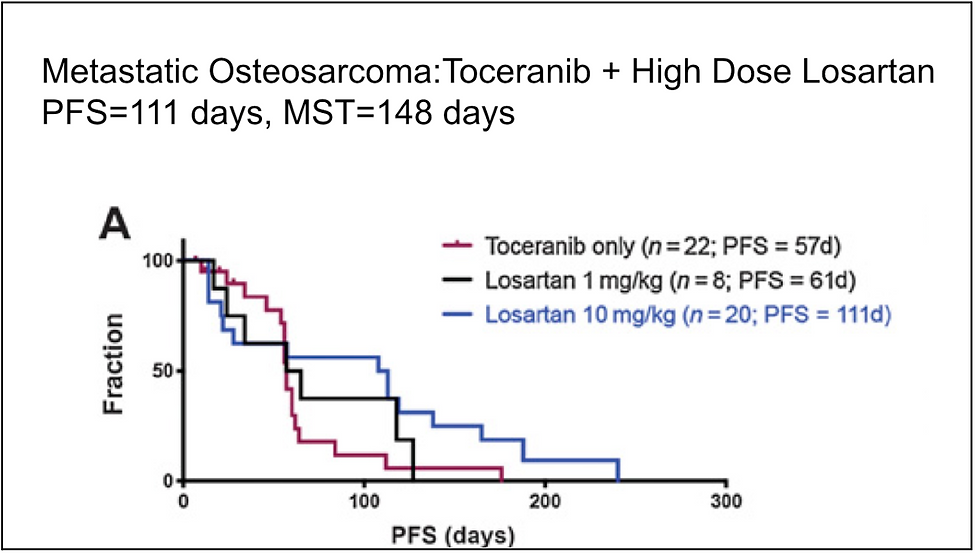

And you can see in this Kaplan-Meier survival curve that after the treatment is started—so these are dogs with metastatic cancer—if you just give them Toceranib or Palladia alone, the progression-free survival is only about 57 days. But if you give them high-dose Losartan and Toceranib, the progression-free survival is 111 days. That’s the blue line here, where you can see that more dogs are surviving longer.

This therapy is another step in the right direction, and it’s a very helpful therapy, especially since these are oral drugs that you could just give at home. It’s not like chemo or anything with strong side effects.

I also want to mention that radiation therapy can have an immune-modulatory effect. Radiation can be stereotactic, giving very high-dose, concentrated treatment in just two or three sessions. Or it could be a more gentle treatment, palliative radiation, where you might get a couple of treatments just to alleviate the pain, or something in between.

Now, the interesting thing about radiation therapy is that it could have an anti-cancer immune effect. Its main job is to try to kill cancer, harm cancer cells, and disrupt the DNA, but it can actually induce in-situ vaccination. It is effectively vaccinating the patient with his tumor proteins that are released with radiation therapy.

But radiation therapy can also have a pro-cancer immune effect, drawing in bad immune cells like regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells and neutrophils that suppress the immune system.

Researchers are realizing that depending on the dose and the timing, radiation therapy could be very helpful or harmful to the immune system’s fight against cancer.

Many of the studies are being conducted by Colorado State University and University of Wisconsin. But I want to mention a study at Washington State University.

If you joined our last webinars, you’ll remember Mavis’s mom who shared her story. Mavis was diagnosed with osteosarcoma, and she came to one of our fundraising events, a 5K here in Redmond, Washington. Mavis’s mom learned about Professor Mamula’s EGFR/HER2 vaccine trial at Washington State University.

Washington State University Veterinary Hospital is enrolling dogs with osteosarcoma who are not candidates for surgery. These dogs may be too big, or they may have other problems that prevent surgery. They are offered treatment with palliative radiation, the EGFR/ HER2 vaccine, and Zoledronate. No surgery.

This treatment has just minimal side effects. Professor Mamula reported in October 2024 at the Veterinary Cancer Society meeting that the median survival is almost a year.

And this is probably because of the immune-modulating effect of palliative radiation. This is based on only about 11 dogs so they are still trying to enroll more dogs. Mavis survived for about 18 months without having to get an amputation but with the help of this combination of immunotherapy and radiation.

So radiation can have a beneficial immune effect if done right. Some dogs with metastatic osteosarcoma are being treated with some form of radiation therapy and tumor microenvironment (TME) modifying drugs like Losartan, Palladia, and Propranolol.

Ideally, in the future, researchers will develop a way to stop or reverse metastasis without drastic surgeries like amputation.

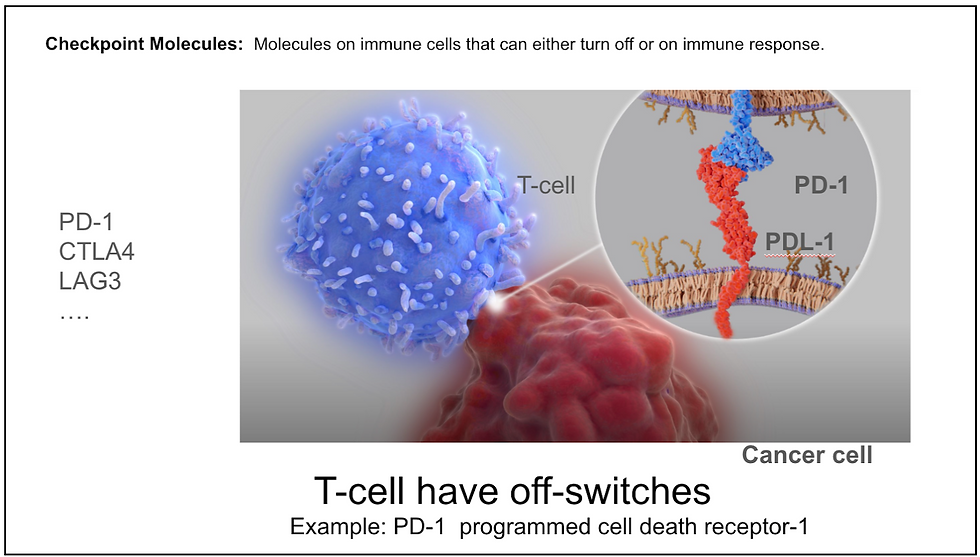

Now, how else does cancer escape being killed by the immune system?

We had a webinar a few months ago on immune checkpoint inhibitors. There is something called checkpoint molecules, and they are basically off-switches for powerful cancer-fighting immune cells like T cells. And they're there because you don't want an immune system to go haywire and attack your healthy tissues. So you have to have an off switch.

But cancer can take advantage of these off switches, these checkpoint molecules, and turn off the immune system.

The good news is that there have been numerous discoveries of checkpoint molecules and successful development of drugs that block them.

So, for example, PD-1 Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor drug can block cancer from utilizing the PD-1 checkpoint molecules to deactivate T-cells. Similarly, CTLA-4 Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Drugs are now available.

You probably heard a few years ago that former President Carter had metastatic melanoma that had already spread to other organs, including his brain, but with the help of PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor treatment, his metastatic melanoma completely disappeared, and he was effectively cured of cancer. It doesn’t work for every metastatic melanoma patient. Only a fraction of patients —maybe 20% depending on what combination is used—are cured.

However, it is still an amazing development that a fraction of metastatic cancer patients are being cured with the help of ICI.

So how about immune checkpoint inhibitors for canine patients?

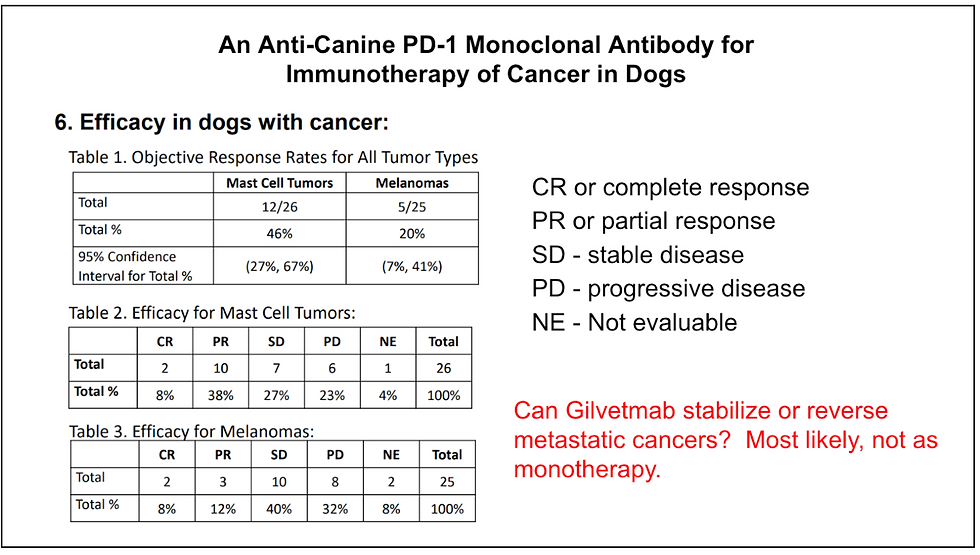

A new drug called Gilvetmab was introduced last year by Merck. It's a caninized PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, and it has conditional approval. So today, any veterinary oncologist in US can place an order. It has been tested with mast cell tumors and melanoma canine patients (stage two and three melanoma patients), and they've published limited data on its efficacy.

And when you look at these numbers here, this table says 20% of melanoma patients responded with either a complete response or a partial response. The bottom table actually is more informative. Complete response was seen in two out of 25 dogs, 8%. Partial response is 12%. Stable disease was seen in 40% of dogs.

Can Gilvetmab or other immune checkpoint inhibitors be used to treat metastatic cancer?

The answer is we don't know for sure. But the answer probably is yes. It may be more effective if it's combined with something else—something like a vaccine or radiation therapy. But by itself, there might be a few lucky dogs with metastasis that might respond to Gilvetmab, and the cancer might go away completely. But probably most of these dogs will need something else combined with Gilvetmab so that metastatic cancer can respond. We are expecting more findings to be published in 2025.

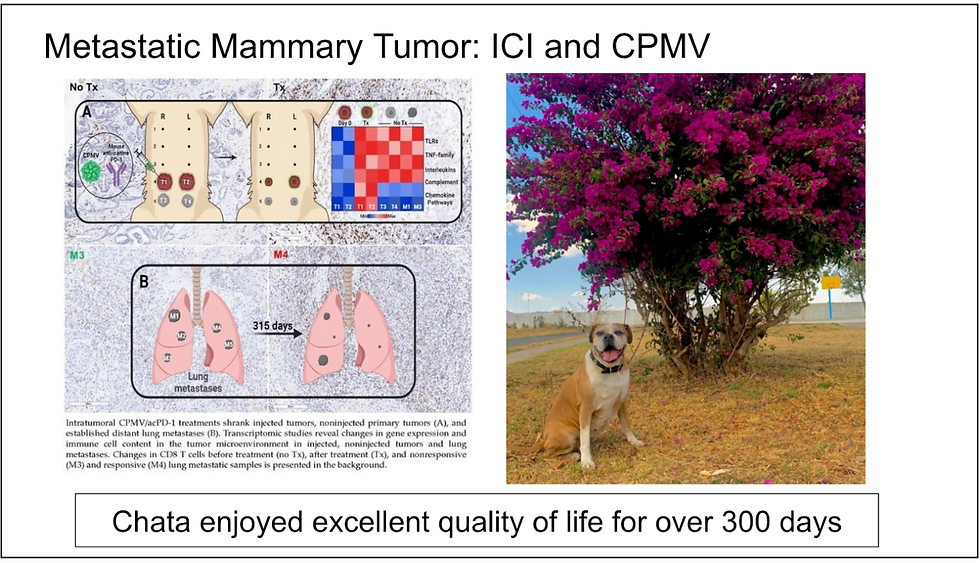

So here is Chata. This beautiful dog had a mammary tumor, and it had metastasized to the lungs. And in this study published by Dartmouth College scientists in 2024, they described that she was treated with PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor with another immunotherapy treatment. This strong immune-stimulating drug was composed of a plant virus, which is harmless to dogs and people but still stimulates the immune system.

When Chata was treated with this combination of immune checkpoint inhibitor and immune stimulator, the lung metastasis stabilized and shrank. One lesion did get slightly bigger, but she survived for over a year with excellent quality of life.

So there’s hope, and we believe that it is possible to do these combinations to successfully treat metastatic cancer.

So looking ahead, how will metastatic cancer be treated (while maintaining an excellent quality of life)?

It’s probably some form of combination approach that’s needed to tackle metastatic cancer: a vaccine or other immune-stimulating agent, maybe with in-situ vaccination—that could be palliative radiation. Maybe cryotherapy—studies are saying that cryotherapy done right will stimulate the immune system in a good way. Electrochemotherapy may also help.

Immune checkpoints have to be addressed with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. And you also need to take care of the tumor microenvironment to remove the immune-suppressing cells.

Finally, I want to share stories of a couple of human patients.

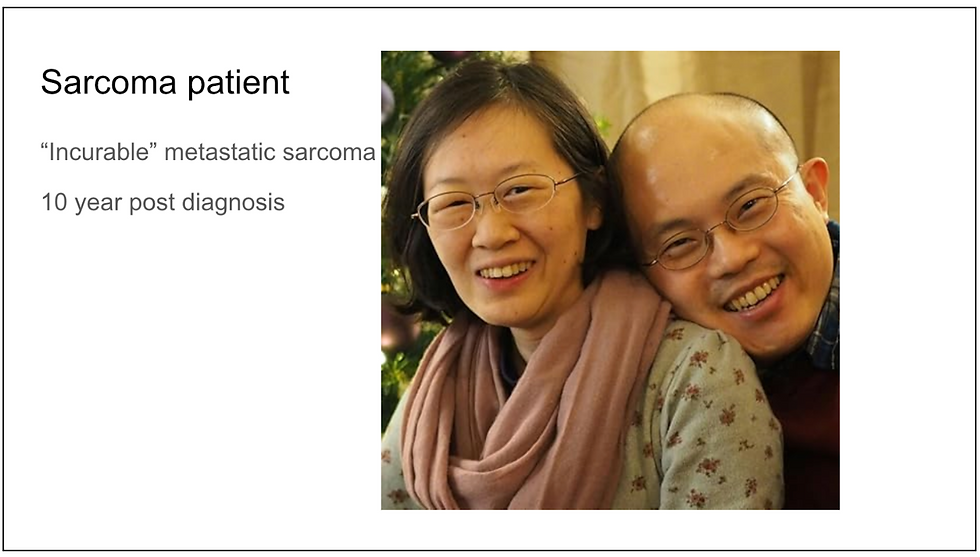

This is Rene Chee. She is a PhD biologist who lived in the Bay Area. And in her 20s, she was diagnosed with cancer on her jaw. It was metastatic sarcoma. Her oncologist said her type of sarcoma was not curable, and she was given a prognosis of only a few years.

But she and her husband began talking to researchers, especially different immunologists and sought out immunotherapy treatments that were not yet widely available in the US. They traveled to Mexico, got Coley’s toxin injections, changed their diet, increased omega-3 intake, and also tried cryotherapy. She is amazingly alive today, more than 10 years after her diagnosis.

Another patient I want to mention is a pediatric osteosarcoma patient. After the University of Pennsylvania ran a study with canine osteosarcoma patients, a pediatric clinical trial was launched for the Listeria vaccine. And Kirstie Gomes - a patient with metastatic osteosarcoma - was one of the patients who received the vaccine. She is still alive today, now almost five years after vaccination.

So I think there’s a lot of hope.

Researchers don’t yet know how to best combine immunotherapy, and how to best modulate the immune system to effectively fight metastatic tumors, but I think over the next couple of years, they will develop effective ways to treat metastatic cancer.

Of course, it’s better to find cancer early and treat it early, but we all know that with our pups, it is extremely hard to find cancer early.

There are some human clinical studies now starting to show that even with metastatic solid tumors, it’s possible to reverse and stabilize or eliminate cancer with the help of combination immunotherapy treatments.

So there is a lot of hope for the near future for our pups.

Thank you so much for joining the webinar. And if you would like to support the projects that we’re funding—including the EGFR HER2 vaccine trial and other studies that are trying to make therapies work better—please join and become a monthly donor.

Check out other articles and videos

Questions? Email us at info@ccralliance, and we'll get back to you as soon as we can!

Canine Cancer Alliance is a non-profit organization supporting research for canine cancer cures.

All information on the Canine Cancer Alliance website is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to be a substitute for professional veterinary advice.

Always seek guidance from your veterinarian with any questions regarding your pet’s health and medical condition.

%20(2).png)

Comments